The onslaught of COVID-19 media coverage, health inequity news reports, and recent personal and professional encounters prompted me to take a hard look at racial bias.

In my opinion, many of us can’t help but bring preconceived beliefs about race, ethnicity, religion and sex, among other topics, to life situations and experiences. I am not the first one to say this, but racial bias and racism are pre-existing conditions.

Many of those biases are stereotypically negative and based on ignorance and a lack of awareness about people different than ones that are in an individual’s “circle of comfort and familiarity.”

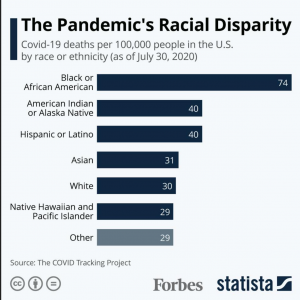

Simply put, the pandemic is disproportionately ravaging and killing Black and Brown people. The reasons are complex, but the root cause is, at least in part, attributed to historic and systemic racism. The by-products of such bias touch every facet of racial minority life in America. Yes, the disparities that exist between People of Color and White people have been exacerbated by the pandemic.

The residual effect is chilling.

I read “Pandemic Brings out Biases Experienced by Minorities” today in Philadelphia’s daily newspaper, The Philadelphia Inquirer. The article, for me, was confirmation and validation of what Black and Brown people have always known to be true. Using the experience of Karla Monterroso as a backdrop, the article explains:

“Because when we go and seek care, if we are advocating for ourselves, we can be treated as insubordinate…and if we are not advocating for ourselves, we can be treated as invisible.”

“Her experiences, she reasons, are part of why people of color are disproportionately affected by the coronavirus. It is not merely because they are more likely to have front-line jobs that expose them to it and the underlying conditions that make COVID-19 worse.”

“That is certainly part of it, but the other part is the lack of value people see in our lives,” Monterroso wrote in a Twitter thread detailing her experience.”

”Research shows how doctors’ unconscious bias affects the care people receive, with Latino and Black patients being less likely to receive pain medications or get referred for advanced care than white patients with the same complaints or symptoms, and more likely to die in childbirth from preventable complications.”

Karla’s story made me angry. It made me feel a profound resentment and disgust for what is undeniably a more devastating and enduring threat than the pandemic — racial bias.

I realize that I am blessed. I do not face home or food insecurity. I have medical coverage. Tomorrow I will go to work, turn on and sit in front of my computer.

But the kick in the gut occurs when I think about those whose means are less than mine. I think about my sisters and brothers who suffer with higher infection rates…lower paying and riskier jobs…inadequate or sub-par public services…and daily face the scourge of a pandemic that affects in profoundly disproportionate ways.

I feel resentment and disgust for what is undeniably a more devastating and enduring threat than the pandemic…racial bias in America.

The pandemic and similar misfortunes reveal the underlying dark truth of racial bias.

We can do better.

We have to do better.

Because?

Our lives matter.