I didn’t know Charles Roberts, my paternal father.

My mother divorced him when I was a toddler.

Upon reflection and an examination of the facts, as I recall them, my father did very little to foster a relationship with me.

In fact, my father’s most important relationship was with alcohol…and, ultimately, it is the thing that took his life. He drank himself to death.

Much of the credit for the man I have become is due to my mother.

A single Black female, full of grit and moxie, determined to make a good life for herself and her son. She is part of a legacy of strong Black women who wore multiple hats, made sacrifices and like a momma bear, nurtured and protected her cub.

Credit is also due to a man named James Burks.

My mother didn’t have a lot of boyfriends.

There were, of course, men that she dated, but “Mr. Burks+” was somehow a consistent presence in our lives.

He was the only constant adult male in my life while I was growing up.

As far back as I can remember, he always treated me with love, respect and dignity. He treated me as if I were his own flesh and blood.

I questioned him about that recently and he replied,

“What was I supposed to do? I was dating your mother and had no choice but to love you and fill the void that was there. You needed me.”

Over time, to the outside world, including family and friends, Jim Burks was my father. To me he was Dad.

He taught me how to properly care for myself – things, I assume that men teach their sons – how to shave, how to groom and. most importantly, how to best navigate through life as a Black man. Who better equipped to teach a young Black man these lessons than another Black man?

There are countless snapshots and memories from the past that solidify his presence and importance in my life.

An appreciation of the arts, mostly music: introductions to James Baldwin, Billy Strayhorn, Coltrane, Billie Holiday, Puccini, the simplicity and vibrancy of a Harold Wheeler string arrangement. He was passionate about history and antiques and he shared his passions with me. Like a sponge, I absorbed them all.

Education: He hired a tutor for me when I needed to improve my grasp of arithmetic.

When my boarding school tuition was due and my mother was short, Jim made up the difference and added a sweetener on top.

In my early teenage years when my maternal grandfather’s body was riddled with cancer and he was dying, it was Jim Burks who showed up at school to take me to Boston in order to say goodbye. He didn’t tell me “how to” mourn, but through his actions, he taught me that it is okay for a man to be vulnerable, to cry and express empathy.

My mother and Jim came to visit me in the eighties. I was in my twenties, living in New York – in an apartment that I could not afford, in a relationship that was toxic and detrimental to my well-being, and visibly thin and in trouble.

Disgusted and disappointed by what he saw, Jim called me later and told me to pack up my things. He was coming to take me home. On the appointed day with no more than a hello, we loaded his car with my belongings and he brought me home. The two-hour car ride was filled with silence.

All that was needed to be said remained unspoken. He rescued me. He saved my life. He saved me. He showed up when i needed him most.

Eight months ago, I got a telephone call from my dad’s doctor…He was concerned that he had missed two appointments.

“These are radiation treatments for the skin cancer, Eric. It is important that Dad not miss these appointments. They are scheduled every weekday for the next two weeks, and you have to make sure he gets there.”

Skin cancer? Radiation? This was new information to me.

When questioned, my dad made light of the situation and referred to the treatments as “this thing.” He saw it as no big deal and, at 95 years of age, I assumed that, given all that he had been through in his life, it was no big deal. So, for two weeks we would go to the oncology treatment center at the hospital. Outwardly he appeared fine and without any visible side effects.

Three weeks later, everything changed and the world turned upside down.

+As a child, I was instructed to refer to any adults as “Mr” or “Miss.” My mother believed that it was not only a sign of respect, but, in her mind, a differentiator, that separated her child from others. So for close to twenty years, I referred to my dad as “Mr. Burks.”

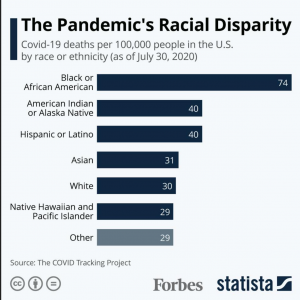

We tend to become emotionally involved when something is personal. The loss of friends and loved ones to HIV/AIDS over the course of thirty years produced a perpetual cycle of loss, pain and goodbyes. It was the start of my emotional involvement and decision to speak up and do something.

We tend to become emotionally involved when something is personal. The loss of friends and loved ones to HIV/AIDS over the course of thirty years produced a perpetual cycle of loss, pain and goodbyes. It was the start of my emotional involvement and decision to speak up and do something.